Atrial Flutter

Atrial Flutter is a common heart rhythm abnormality due to an electrical circuit in the atria at the back of the heart.

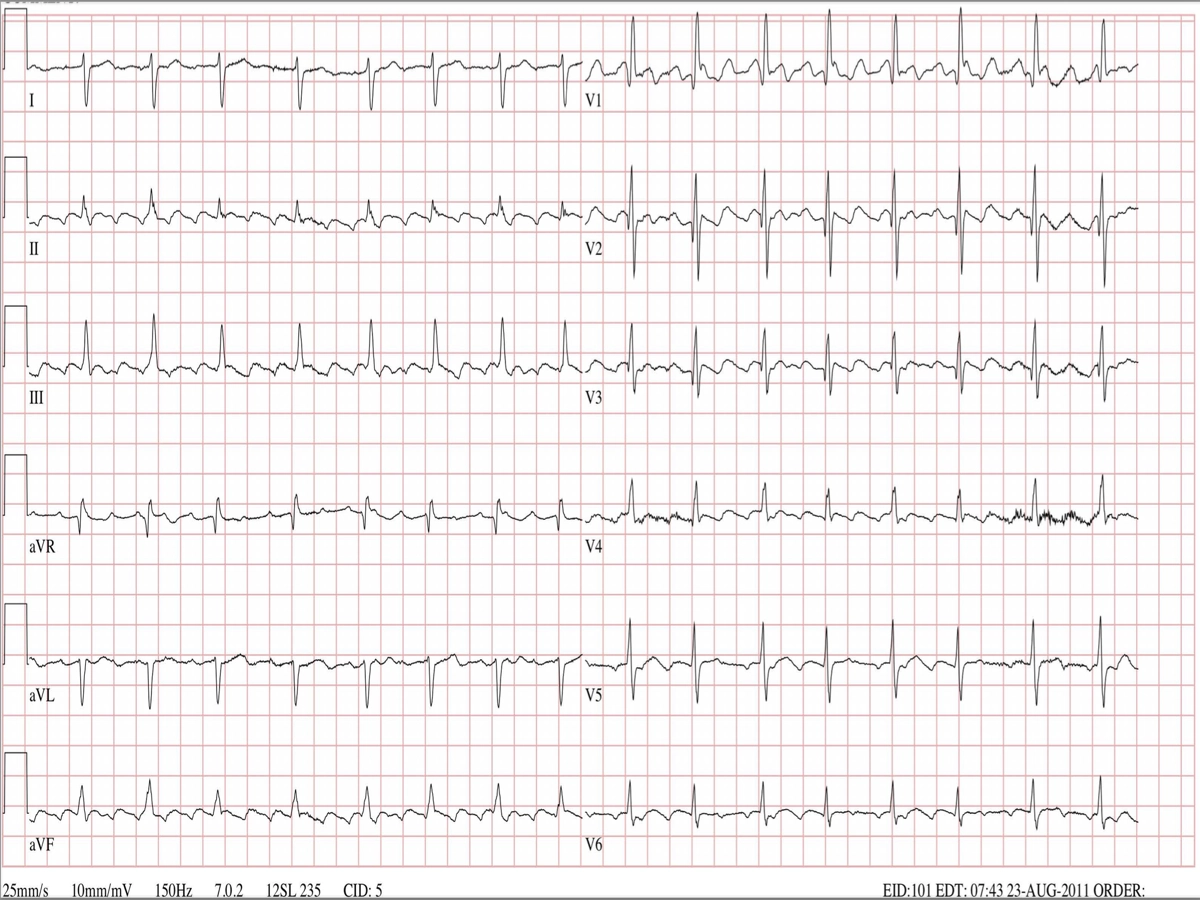

Typical Atrial Flutter on ECG

Symptoms

The most common symptom is palpitation (an awareness of a hard or rapid heart beat). It may also cause shortness of breath, or fatigue. In some cases it causes no symptoms at all and is picked up incidentally.

Types

There are two forms of atrial flutter. Typical Atrial Flutter is due to an electrical circuit that passes around the tricuspid valve on the right side of the heart. The tricuspid valve sits between the right atrium and right ventricle. Atypical Atrial Flutter is due to an electrical circuit anywhere else in the atria. The ’typical’ form is more common, and more easily treated.

Diagnosis

Atrial flutter is diagnosed on an ECG, rhythm tracing, or a 24 hour Holter. Increasingly, home ECG monitors such as the Apple Watch or Kardia AliveCor ECG make the diagnosis.

Why Does It Occur?

Most people with atrial flutter will have a history of heart disease - such as coronary artery disease, previous cardiac or valve surgery, or cardiomyopathy (weakening of the heart muscle). However, it may also occur without apparent cause.

Almost all episodes are triggered by atrial fibrillation. That is, atrial fibrillation, which is a chaotic irregular rhythm from the atria, organises into atrial flutter which is a more ordered regular rhythm in the atria. The episode of atrial fibrillation is often short-lasting, and by the time an ECG is performed the atrial flutter is already present.

Treatment

-

Protect Against Stroke: As the atria are beating rapidly, and because most episodes of atrial flutter are triggered by atrial fibrillation, there is a risk of a blood clot forming in the atrium. Markers of higher risk that would indicate using an anticoagulant medication (e.g. rivaroxaban, apixaban or dabigatran) to prevent a blood clot include: heart failure, high blood pressure, age > 65 years, diabetes, vascular disease, and previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack.

-

Slow the Heart Beat: If the pulse rate is high, you may be placed on a heart rate slowing medication. Typical examples include the beta blocker group (atenolol, metoprolol, bisoprolol) or a calcium channel blocker (verapamil or diltiazem). In some cases, amiodarone or digoxin are used.

-

Decide on Cardioversion or Catheter Ablation: If atrial flutter is asymptomatic, and the heart is working well, a decision may be made to ’live with the condition’. But most people will feel better in normal rhythm and in that case a decision between DCR (cardioversion) and catheter ablation is made. Both of these procedures get the heart back into normal rhythm.

DCR vs Catheter Ablation

DCR is a simple procedure, performed after a suitable period (3-4 weeks) on blood thinning medication. After fasting, an anaesthetist will deliver a general anaesthetic for 5 minutes or so. An electric shock is delivered to the heart to get it back into normal rhythm. DCR has the advantage of simplicity, and may be reasonable after a single episode of atrial flutter, but it does not do anything to keep the heart in normal rhythm. It is probable that atrial flutter may recur sooner or later. The Risks of the procedure include: reaction to anaesthetic, and stroke (which is very rare if anticoagulation is strictly adhered to both before and after the procedure).

Catheter ablation is a potentially curative procedure for atrial flutter. Under general anaesthetic, thin flexible wires are delivered through the femoral vein in the leg up to the heart. An ablation catheter delivers radiofrequency energy (heating) which eliminates the electrical circuit. If “typical” atrial flutter is present, the cure rate is 90-95% on the first procedure. “Atypical” atrial flutter has a lower success rate around 70-80%. The advantage of this procedure is that it both gets the heart back into normal rhythm and stops it going into atrial flutter again.

Possible complications of catheter ablation include bleeding/vascular complications at the femoral vein, need for a pacemaker (0.5%), pericardial effusion (fluid around the heart); more serious risks such as stroke, heart attack and emergency surgery are rare, 1 in a 1000).

As stated above, most cases of atrial flutter are triggered by atrial fibrillation. Catheter ablation of atrial flutter does not fix atrial fibrillation. There is a rough rule of thirds: about 1/3 of people will have troublesome atrial fibrillation even though the flutter is fixed; 1/3 will have atrial fibrillation which is much less symptomatic than the atrial flutter; and 1/3 will have no or little AF and effectively remain in normal rhythm most of the time.

What this means is that some people who initially have a good result from atrial flutter ablation will go on to need treatment for atrial fibrillation.

If atrial flutter comes and goes, this generally means that AF will be a problem and it is usually better to treat both atrial flutter and fibrillation at the same time i.e. catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. But if atrial flutter is stable and chronic (i.e all ECGs show atrial flutter over weeks to months) then it may be reasonable just to treat the flutter first and then carefully observe.

Summary

Atrial flutter is a common arrhythmia arising in the atria at the back of the heart. It often necessitates oral anticoagulation to prevent a stroke, and medication to control the heart beat. In most cases, a DCR or catheter ablation is performed to get the heart back into rhythm.