Supraventricular Tachycardia

Supraventricular tachycardia is a rapid heart beat causing palpitation, dizziness, shortness of breath, and occasional fainting.

Anatomy

There are four chambers in the heart: two atria at the back, and two ventricles at the front. The atria lie slightly above the ventricles. Therefore, abnormal rhythms that start in the atria are termed ‘supraventricular’, and because ’tachycardia’ is the medical term for fast heart beating, this form of arrhythmia is called ‘Supraventricular Tachycardia’.

Symptoms

The most common symptom is palpitation. During an attack you may feel dizzy, or short of breath, or feel a sense of ‘dread’. Uncommonly, the dizziness may progress to a complete faint.

As SVT is generally short lasting, it does not cause damage to the heart.

Diagnosis

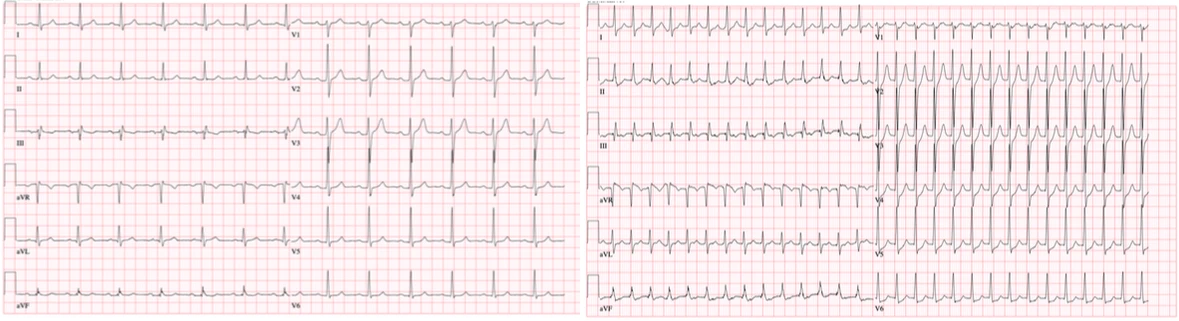

SVT is diagnosed on an ECG. Historically, this was most likely recorded in a hospital or medical facility. But it is now common to record an ECG on a smart watch or other portable ECG monitor.

A formal ‘12 lead’ ECG provides the most information about an SVT, often allowing us to diagnose the specific type of SVT.

Types of SVT

AV node reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT) is the most common form; this is also the type most likely to cause dizziness or fainting. In this arrhythmia the circuit lies very close to the AV node in the middle of the heart.

Accessory pathways, which when seen on a resting ECG is called Wolff Parkinson White, are the second most common SVT. In most people there is a single electrical pathway connecting the atria at the back of the heart to the ventricles. An accessory pathway describes the situation where there is more than one pathway. Electrical signals may pass down the normal AV node and back via the accessory pathway setting up a short-circuit that causes the heart to beat quickly.

Atrial tachycardia refers to SVT which arises in the atria, usually from a focus source. This irritable area fires off beat after beat causing the heart to race. Atrial tachycardia may be found anywhere in the atria.

Treatment

SVT is a generally benign arrhythmia in regard to outcome - it does not cause stroke or heart attack, and dangerous heart rhythms are exceptionally rare.However, the symptoms can be distressing.

There are three main approaches to treatment:

-

Observe and treat as needed: In this approach, you will not take daily medication or have a procedure, but instead treat episodes when they occur. There are some methods that will terminate SVT without needing to go to a hospital; these are termed ‘Valsalva’ manoeuvres. The most common method:

-

Sit or lie down. Hold your nose and try to push the breath out while keeping your mouth closed. You should be aware of a ‘bearing down’ feeling, and strain through your core. Try and hold for 15-20 seconds.

-

If this does not work, repeat the manoeuvre, but this time get someone to lift your legs up after you have finished the breath-hold.

This approach is reasonable if your SVT is infrequent, or can be terminated reliably with Valsalva manoeuvres.

-

-

Daily Medication Two classes of medication are used to prevent SVT:

- Beta blockers - these agents (e.g. metoprolol, atenolol, bisoprolol) slow your resting heart beat, and slow electrical conduction through the heart. They cannot be used if you have asthma. Common side effects include fatigue, exercise intolerance, and weight gain.

- Calcium channel blockers (e.g. verapamil, diltiazem) work in a similar way to beta blockers. Common side effects include: constipation, headache, ankle swelling, and dizziness.

-

Catheter Ablation

Catheter Ablation of SVT

Catheter ablation is a procedure to cure SVT. It may be performed under general anaesthetic or conscious sedation and usually takes 1-2 hours.

If you are on medication to treat SVT, this is generally stopped 3-5 days prior to the procedure.

The ablation is performed either under conscious sedation (’twilight’) or general anaesthesia. Your particular anaesthetic will be discussed prior to the procedure.

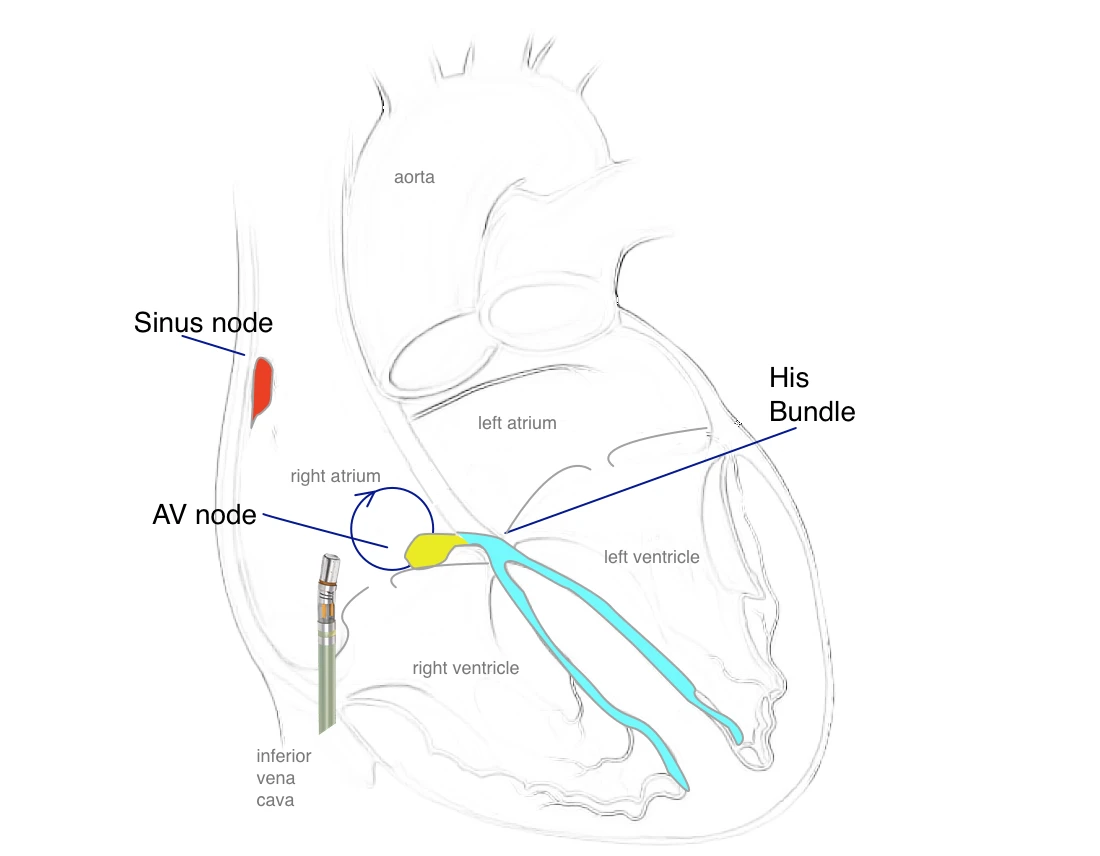

Thin wires (called catheters) are inserted through the femoral vein. This vein lies near the groin on the front of the leg. The catheters are manoeuvred to the heart under Xray guidance, or by using a specialised ‘electroanatomic’ mapping system.

The catheters are then used to stimulate the heart to try and induce the SVT. When the site of the SVT is found, a small current is delivered through the wire which heats up the tip and ‘burns’ the heart tissue thus eliminating the SVT circuit.

Catheter ablation of SVT. Ablation catheter is inserted through the inferior vena cava to the right atrium to treat a SVT circuit arising near the AV node

Tests are then performed to determine if the SVT has been treated effectively. At the end of the procedure all of the catheters are removed from the body.

If the SVT can be induced during the procedure, the cure rate is above 90%. Occasionally, the SVT cannot be induced so no treatment is given.

After the Ablation

You may be discharged the same day or admitted overnight. You should take it easy for a few days - but not rest in bed. You will have a small water-proof dressing over the femoral access site. This allows you to shower, and may be removed after 2 days. Don’t submerge the wound under water for 1 week.

Walking and general daily activities are ok, but you should avoid more intense exercise for a week. This is to allow the puncture site at the femoral vein to heal. After a week you may return to moderate exercise - light jogging, cycling - and then to your usual exercise after a couple of weeks.

In general, you will be seen 1-2 months following the procedure.

Risks of SVT Ablation

Bleeding or bruising is common at the femoral vein site. This is usually minor. Less commonly, a clot may form in the vein.

Some SVT circuits lie very close to the normal conduction system of the heart. There is a small risk (0.5-1%) of damaging the normal conduction system which may require implantation of a pacemaker at the time of the procedure.

Fluid can accumulate around the heart (called a pericardial effusion) during the ablation and require drainage.

More serious complications are rare (<1/1000): stroke, heart attack, emergency surgery, damage to the phrenic nerve with paralysis of the diaphragm.