Premature Ventricular Contractions (PVCs)

Premature Ventricular Contractions are a troublesome, but generally benign, arrhythmia which arise in the ventricles at the front of the heart.

What are they?

The normal (‘sinus’) heart beat begins in the right atrium at the back of the heart, passes through the AV node, and spreads to the ventricles at the front of the heart.

This normal wave of contraction may be interrupted by an ’extra’ beat arising in the ventricle. These extra beats are called ‘premature ventricular contractions’ (PVC) or sometimes ‘ventricular ectopic beats’ (VEB).

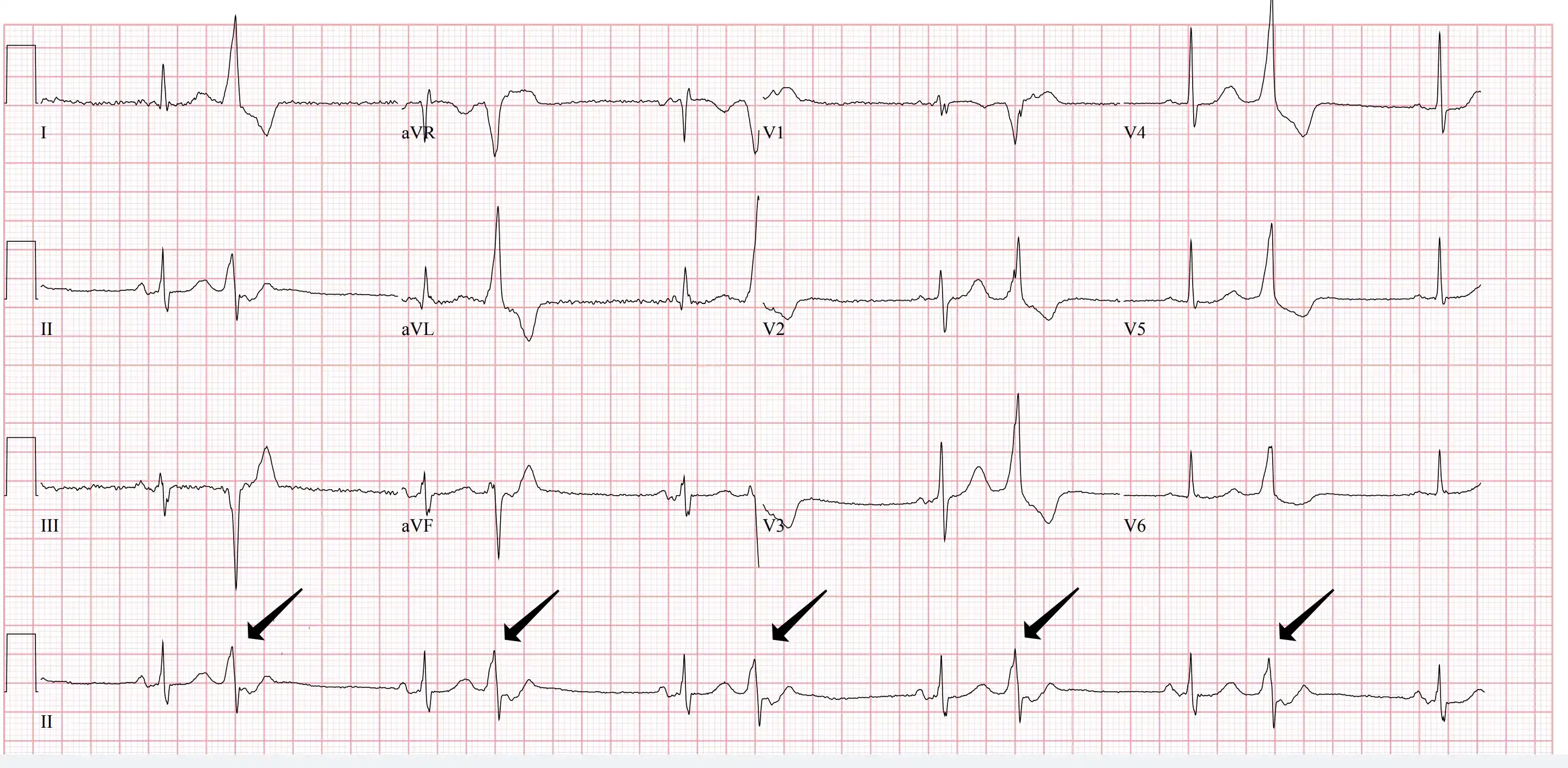

PVCs (arrow) Every Second Beat

Symptoms

There are many different ways that a PVC may present:

- first, they may cause no symptoms at all and only be seen on an ECG or rhythm recording of the heart

- more commonly, they create a ‘fluttering’ sensation in the chest or else the sense of a ‘missing beat’ which is followed by a hard thumping sensation

- less common presentations include a sudden dry cough, a thumping sensation in the neck, sudden dizziness, or shortness of breath

Symptoms often occur when at rest - such as lying down at night, or watching television. During activity or exercise, the higher sinus heart rate may suppress the ectopic beats.

Diagnosis

A PVC is diagnosed on a rhythm recording of the heart. This may be an ECG, a 24 hour Holter or Event Monitor, or increasingly on a smart Watch ECG recording.

Treatment

When PVCs occur in the setting of a structurally normal and healthy heart they are almost always benign. The decision to treat depends on the severity of symptoms.

But when PVCs are frequent (i.e. > 10% of all extra beats) they may occasionally cause weakening of the heart muscle (although most people with lots of extra beats won’t have any dysfunction of the heart). In this case it is important to suppress the extra beats either through medication or catheter ablation. In most cases the apparent weakening of the heart will improve with suppression of the PVC.

Catheter ablation may also be used to treat symptomatic PVCs even when the heart appears normal. The decision to pursue an invasive procedure requires a careful balancing of the benefits (which will depend on the degree of symptoms), against the risks of the procedure. In most cases it is best to try some medication first. But in some people the symptoms of ventricular ectopy are quite severe, the medication ineffective or not tolerated, and they consider the risks of the procedure reasonable in order to improve their quality of life.

Medication

Typical medications include beta blockers such as metoprolol, atenolol, or bisoprolol. These medications may suppress the ectopy, but also render individual PVCs less symptomatic by reducing the force of contraction of the heart. The most common side effects include fatigue, exercise intolerance, dizziness, and worsening of asthma.

Calcium channel blockers (e.g. verapamil or diltiazem) are a second class of medication which may suppress ectopy. The most common side effects are fatigue, constipation, ankle swelling, and dizziness. They may, however, be used in people with asthma.

Flecainide is a more effective medication for the suppression of ectopy, but may only be used when the heart is structurally normal, and there is no evidence of active coronary artery disease.

Catheter Ablation

Catheter ablation is performed in hospital either under conscious sedation or a general anaesthetic. Under Xray and 3D electroanatomic guidance, thin wires (catheters) are inserted into the femoral vein in the groin area and threaded to the heart. A ‘mapping’ catheter is used to localise the origin of the PVC. When found, the catheter tip delivers electrical current to the origin of the PVC thus ‘cauterising’ the tissue. If the PVC is suppressed, all catheters are then removed from the heart.

The risks of the procedure depend upon the site of the PVC. But for all catheter procedures there is a small risk of serious bleeding/vessel damage in the groin, around 1% risk of causing heart block and needing a pacemaker, pericardial effusion (fluid around the heart) which needs to be drained; and more serious risks including stroke, heart attack, the need for corrective surgery if a valve is damaged. Death is very rare (<0.5%). The specific risks will be discussed with you depending on the suspected origin of the PVC.

Summary

PVCs are common. In most cases they may be ignored. While the sensation of a PVC is disturbing, they are generally benign and in up to 50% of cases they disappear without any treatment at all.

But when the symptoms are more severe, or heart function is reduced, consideration is given to regular medication or a catheter procedure.

The video below provides an excellent introduction to PVCs.